In the first part of this article on Story Construction, we considered the basic Plot Points, Story Beats, and Reveals that sit on the Story Arc and are necessary to construct the plot of your story. Now we move on to some more technical, but optional, plot techniques, that will give you story added depth if you choose to use them. We also look at how to start tying together all the different elements that make up your plot, so you can start writing the story.

In the first part of this article on Story Construction, we considered the basic Plot Points, Story Beats, and Reveals that sit on the Story Arc and are necessary to construct the plot of your story. Now we move on to some more technical, but optional, plot techniques, that will give you story added depth if you choose to use them. We also look at how to start tying together all the different elements that make up your plot, so you can start writing the story.

Sub plots

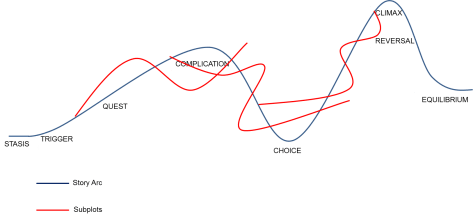

This is another way in which a novel differs from a series of short stories. To make the story more complicated/intriguing/interesting, you may want to include subplots involving some of the minor characters. Each subplot will have its own Story Arc, Plot Points, Story Beats and Reveals. These may or may not correspond to points in the main story, but I think a novel is always more complete if main plot and sub plots do cross at various points.

Think of your novel as a series of related stories, all escalating in difficulty and intensity until the goal is reached. Sub plots are additional, related, short stories that feed into or mirror the main story and usually involve other characters who are in some way linked to the main protagonist or antagonist. Sub plots weave in and out of the main story, sometimes highlighting the main plot, sometimes commenting on it, and sometimes acting as a counterpoint.

Note, all sub plot stories are normally complete by the time the main story hits it’s climax.

As you can see from the above graph, the visual story arc is becoming ridiculously confusing, so at this point in the process I would transfer everything onto a spread sheet. The next elements in creating the look and feel of your novel are unlikely to have their own dedicated scenes, but may not be included in every or selected scenes.

Depending on the size and importance of your sub plot, you will include just enough Plot Points, Story Beats, and Reveals to tell, or perhaps only hint at, the story of the sub plot. However, and this is very important, as the author you need to know (and have plotted out) the full story of each sub plot just as meticulously as you have done with the main story. Sub plots need to be subtle, so you may only sketch out the sub plot story in the main novel, but you still need to know the full story of the sub plot or else it will not work.

Never have a sub plot with more than a third of the Plot Points, Story Beats, and Reveals as the main story. Otherwise it will compete for attention with, and detract from. the main story

So when you construct your story, the sub plot scenes will be scattered around the scenes of the main story/plot. Some of these sub plot scenes will be next to each other, some sub plot scenes will have a number of main story scenes between them, and scenes from several sub plots will overlap. If you are clever, then some of the drama/action/side action in main story scenes will also be sub plot scenes.

If you are subtle enough with your sub plots – unless they are large sub plot like a love story – your readers will hardly notice them. Instead they will just know that your novel has ‘depth’.

Theme

There is no requirement for your novel to have a theme, but you may find you novel has more depth and meaning if you do include one. Also, through reading your story, your reader will be taking on your exploration of your theme with you, which for some authors is the essence of writing.

A theme can be anything and may have no direct connection your plot: the nature of X, life and death, what if Y happens, what if the world was like Z, or an aspect of your protagonist’s/antagonist’s character.

I think a theme says more about a writer’s motivation than anything else – the fact I’m interested in a themes also says a lot about me too.

In my own writing I tend to explore two different, but not unrelated, themes.

The first is belief. I have a real interest in what makes people do the things they do. The things we believe, mould us into the people we are and drive the things we do. Everyone has a worldview, a filter or lens, through which they seek to understand the world in which they live. No one is without belief, even if that belief is in ‘nothing’.

The second is morality: how far will people go before they undermine their their own moral stances.

If you want to know what someone really believes or what to examine their morals, put them in an extreme situation and see how they react. Often, what they say they believe won’t match with what they actually do when they are under pressure; which means what they actually believe, isn’t what they say they believe, or maybe even believe they believe. Showing this moral erosion or the sacrifice required to maintain the moral stance, in a story, makes for great fiction.

In my second dystopian steampunk novel, Coggler’s Brood, the plot is about the protagonist, trying to deliver a package given into her care, but the theme is, ‘How far will she sink morally to thwart her mother’s evil plans.’ In essence, my theme is to explore an aspect of my protagonist’s morals – will she stoop to the monstrous depths of her mother in order to overcome her mother? If not, how far will she go? Where will she draw the line? Ideally, my aim is to leave readers pondering their own morals and questioning how far they would stoop to save the world, but it may just leave them wondering in what ways morally they resemble like their parents. In either event, I, the author, will have had an impact on the reader and therefore the world.

To borrow a weaving metaphor, your theme is the warp on which the weft of your story is built, it’s pattern may, at some point, impact your plot, but maybe not directly. Alternatively, the theme may be hardly noticeable initially, but by the end of the story the entire plot may revolve around your theme.

Working a theme into your story is a relentlessly subtle process, with one golden rule: you can never actually state the theme, or have a character state the theme.

For a satisfying reading experience, the reader must discover the theme for themselves – they must extrapolate the theme from the actions and character development of the novel in its entirety, i.e. the theme must be expressed and developed through ‘showing’ not ‘telling.’

Developing the theme of a novel is like a dripping tap/faucet: slow but relentless. Everything in the author’s technical tool box need to be deployed in developing your theme. Your character’s point of view, the challenges you give them, their decision/choices, your writing style, sentence structure, and word choice all play a part in weaving the theme into your story. You may want to include certain descriptions, metaphors, smilies, or turns of phrase to enhance your theme. Just choosing to use a certain set of words related to your theme can help to set the thematic tone.

If you are determined, you may need to devote an entire edit of your novel to theme development. This is one of the story layers that can easily be added in after the main draft is finished or which can be planned into your initial master plan before you even start writing.

Symbolism

Like theme this is an optional element to your story, possibly a hidden element, which is drip fed into the main story. You may decide you want to place certain objects into the story to give it symbolic meaning. Just like with the theme, you may want to include certain descriptions, metaphors, smilies, or turns of phrase to enhance your symbolism. What about choosing something symbolic for your character(s) to wear – no need to explain them, just the fact they are there can add to the symbolism of your story. Symbolism is not something I have yet experiments with yet, but I understand the theory.

Timeline

You should by now start to have a good handle on your story, but one thing which is essential, and may prove quite challenging, is to devise a timeline for your story. Over how long is this story taking place? Decades, years, months, days, hours? It makes a difference to the way you tell your story and its intensity. If you have no idea of the timeline for the story arc, neither will you readers. That may not matter in some instances, but to your reader is wil mostly just look like holes in your plot.

Tying It All Together

This is where your imagination can go into overdrive and you start constructing your scenes. In tying together all the points on your story arc, the thing to remember is that every Plot Point, Story Beat, and Reveal, must relate to both the item before it and the item after it in a logical progression, to form a complete coherent story. Getting from one item to another may be a simple step or may require a number of different scenes.

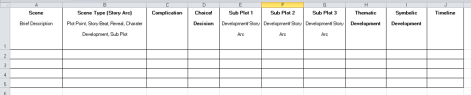

As I said before, I find a spreadsheet to be the most useful tool at this point. The spreadsheet will grow further once we construct our characters, and talk in detail about scene construction, but for the moment the headings on my spreadsheet will start to look something like this:

The image is a bit small so here is the list of headings on our spreadsheet so far:

- Scene – Brief Description

- Scene Type (Story Arc) – Plot Point, Story Beat, Reveal, Character development, Sub Plot

- Complication

- Choice/Decision

- Sub Plot 1 – Development/Sub Plot Story Arc

- Sub Plot 2, 3 ,etc – as many or as few as you want, just remember to list them all

- Thematic Development

- Symbolic Development

- Timeline

Each scene, except the first and the last, will also have to relate to the one before it and the one after. Of course, in the finished novel there is no requirement to show all the scenes in chronological order, or even to include all the scenes, but at the planning stage the author does need to know/understand how the whole story fits together.

If you are anything like me, once you have an idea of where your story is going, you will probably have started to write out some of the key scenes along the story arc. Let’s face it, that’s the fun part; that’s why we write.

Now you need to tie all the scenes together and plan how you are going to get from one scene to another.

If you can’t work out a particular scene flow, then work backwards. What has to happen in scene Y in order for scene Z to happen, what has to happen in scene X for scene Y to happen, what needs to happen in scene W… you get the idea. We will look at scene construction in more detail in another article.

Learning The Skills

Learning how to weave together all the different elements of a novel length plot, the story arcs, the character journeys, sub plots, etc, is a skill particular to novel writing that you will have to learn and practice.

One way to do this is to write novellas (stories 20,000 – 30,000 words in length), that way you can practice writing lots of stories with a novel type structure. You can always do a series and string them together as a full novel later on with a common theme/aim. I wish someone had advise me of this early on in my writing journey – instead I launched into writing a full 80,000 word novel. My learning curve would have been much shorter if I had written smaller novels more frequently. For instance, tying together all the different strands at the end of the story, is a particular skill, if I had written novellas, I would have had more practice in this area.

In the next article we will start to construct our characters.

Image credits

- Dripping Tap Gif: Wikimedia Commons

- Weaving: Gifsoup

- All other images: my own

Previous Posts in The Novel Writing Series

1. Writing Workshop – Constructing a Novel

2. Writing Workshop – Constructing the Story – Part 1